Author: Tanja Maljartschuk

Translator: Zenia Tompkins

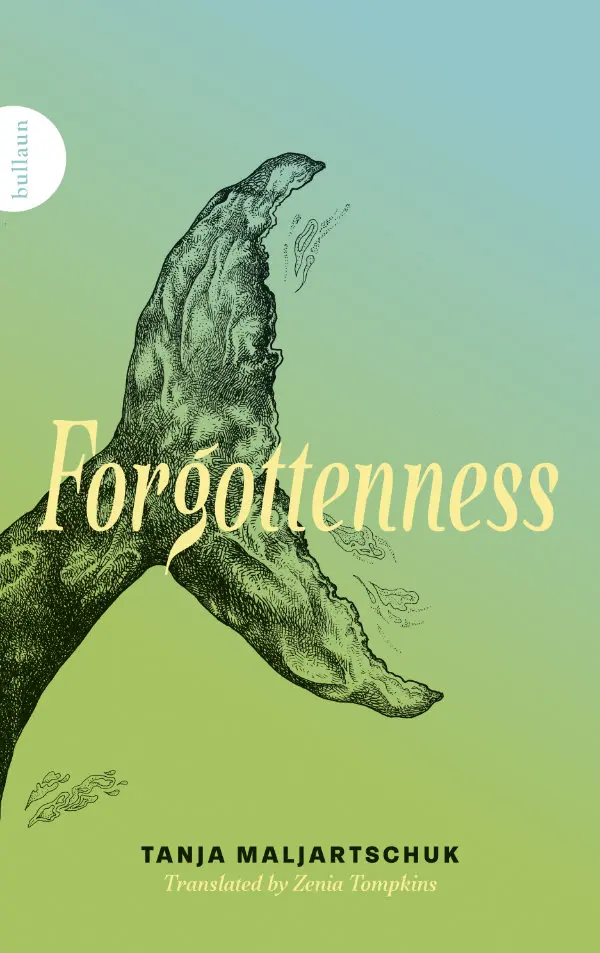

Two tales intertwined in a profound double portrait, Forgottenness painstakingly traces parallels between the historical and the contemporary, the collective and the individual, between the stories of two people born on the same day, a century apart.

The narrator, a writer grappling with her growing anxiety and obsessive thoughts, becomes fixated on Viacheslav Lypynskyi (1882–1931), a once-significant figure in the struggle for Ukrainian independence who has since fallen into oblivion, into the gaping mouth of Time.

As she plunges into her nation’s history to come to terms with her own, we slowly uncover the complex relationship between time, memory and identity to confront the question – what does it mean to remember?

“Time is a big blue whale. It devours me …”

Winner of BBC Ukrainian Book of the Year Award (2016)

Winner of Usedom Literature Prize (2022)

Publication date: 29 February, 2024.

Cover design by Niall McCormack. Cover illustration by Anastasia Melnykova.